A rare exhibition of prints, woodblocks, watercolours brings to light the perspective of Colonial India through the eyes of travelling artists from around the world

The Garden of the Director’s Residence, The Sir J.J. School of Art, Bombay, Charles Gerrard, oil on masonite. Pics courtesy/DAG

This writer remembers when the most prized titles on the book shelf at home would be his father’s collection of Paul Scott’s Raj Quartet. It evokes a nostalgia, though tinged with Colonialism. A peek into the works on display at DAG’s upcoming exhibition, Destination India: Foreign Artists in India, 1857-1947, that opens tomorrow offers a similar déjà vu. Giles Tillotson, curator and senior vice president, DAG, has been at the helm of putting this vast collection of around 100 works together.

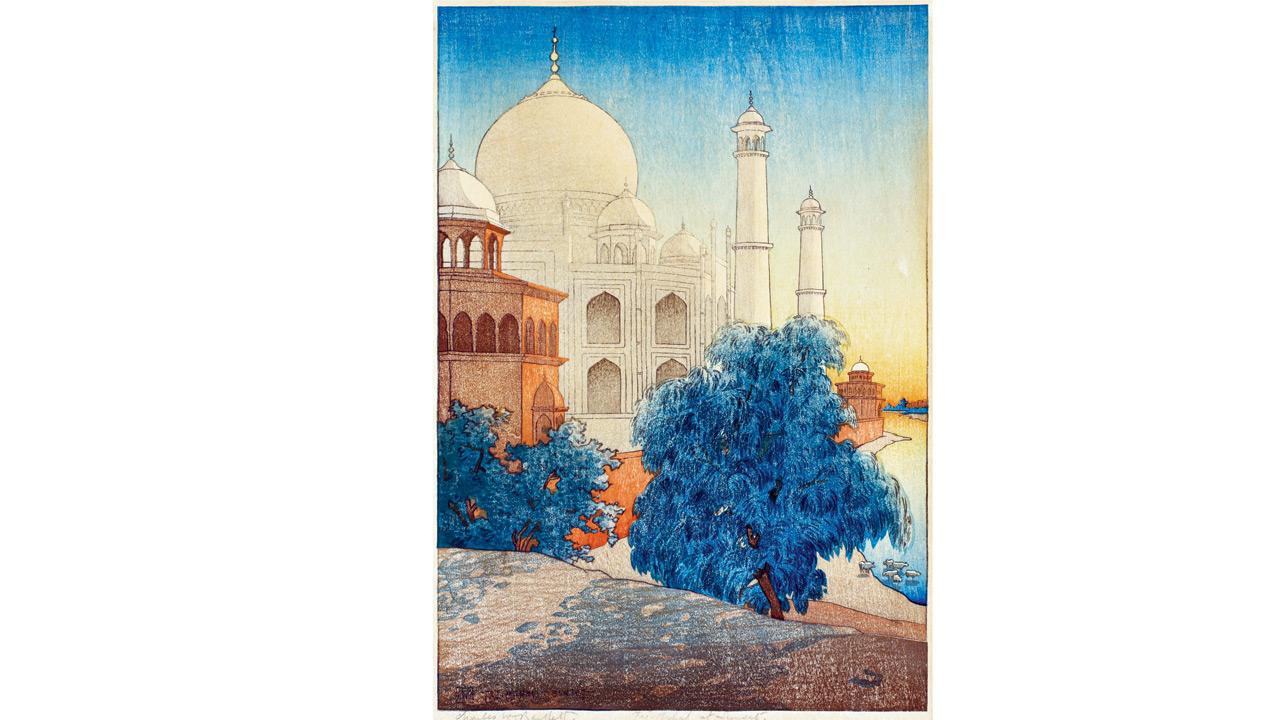

Taj Mahal at Sunset, kokka woodblock print on paper, 1919, Charles William Bartlett

For a long time, there has been a general myth among art historians that the attraction of India diminished for artists post the 1857 War of Independence, owing to the rise of photography. But Tillotson observes, “As I began to oversee acquisitions, there were names we had not always heard of. There was a story to tell, not that artists had stopped coming to India, but that they were coming from diverse parts of the world.”

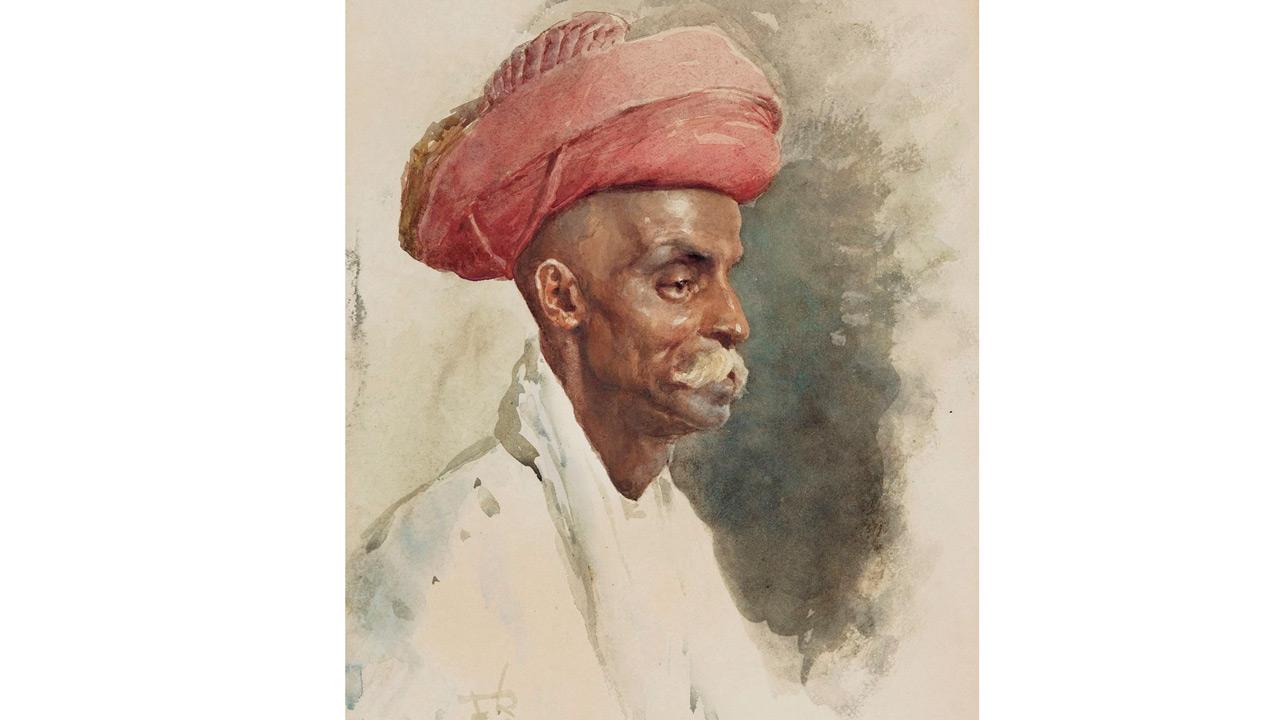

These included Charles William Bartlett, Alfred Edward Emslie, Marius Bauer, Cecil Burns, Edwin Lord Weeks, Erich Kips, Hugo Vilfred Pedersen and Hiroshi Yoshida to name but a few. These were American, Dutch, Danish, and Japanese artists moving through the heartland of India.

A changed perspective

The challenge of photography also shaped their perspective. “It was no longer an enlightenment or explanation of the Orient but a much more individual response to different experiences,” Tillotson points out. As an example, he points to William Hodges’ first visit to the Taj Mahal in 1783.

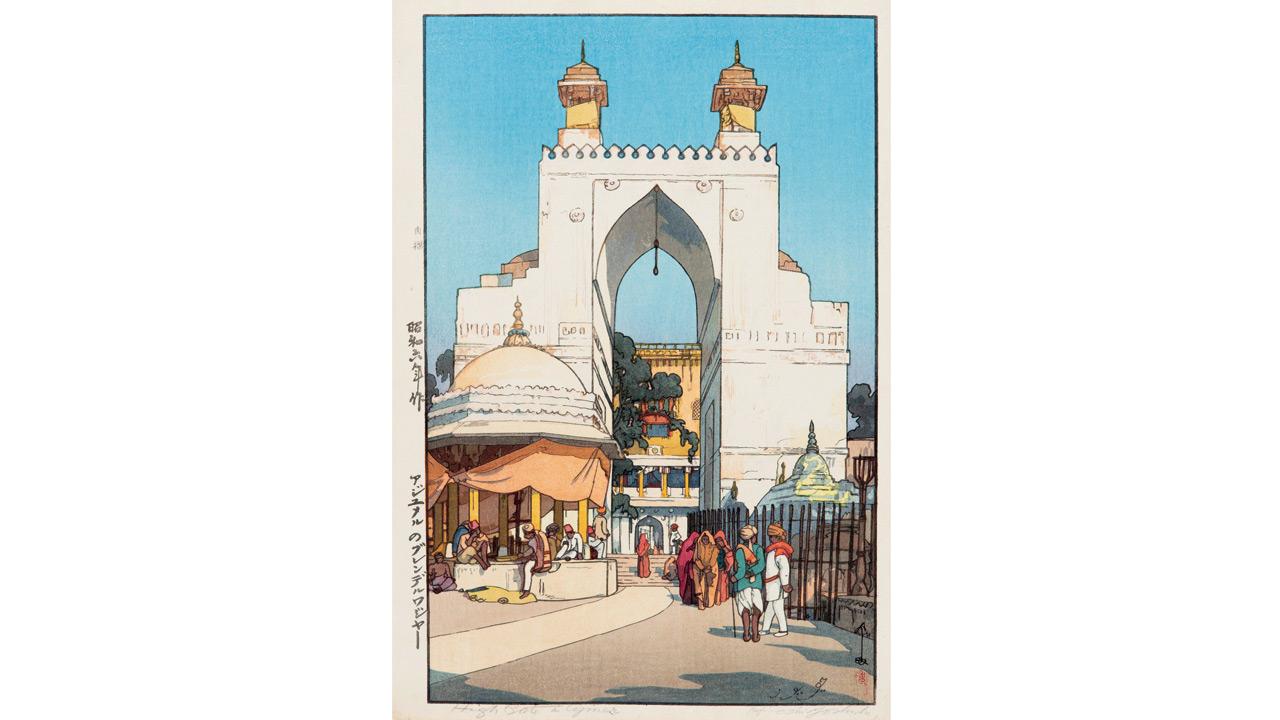

Ajumeru no Burenderuwajaa/High Gate in Ajmer (Buland Darwaza of Ajmer), Hiroshi Yoshida, kokka woodblock print on paper, 1931

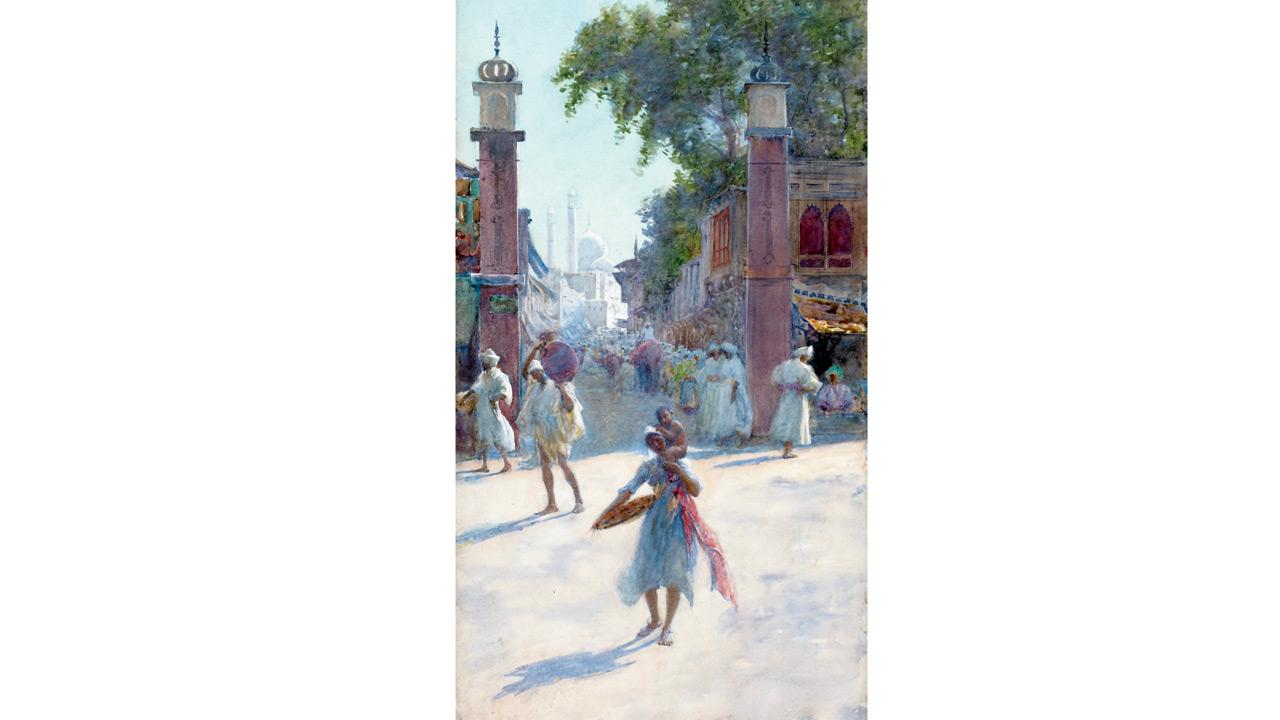

“Hodges is the first artist to ever visit the Taj Mahal. He was producing work for an audience that had heard of the Taj Mahal, but never seen an image. By the time William Simpson and Edward Lear visit, a century later, it has become a cliché,” he states. And so, the works become individual perspectives offering a glimpse of marketplaces, people, landscapes and culture — vibrant in colour, culture and texture of life. The locations were just as new as the perspective.

Exotic not colonial

The meagre presence of Colonial epicentres such as Bombay in the works evokes our curiosity. “The artists were looking at Bombay as another European city. They are in search of subject matters that are more exotic,” the curator adds. While Delhi, Agra and Benares continued to fascinate them, the period turns attention to destinations such as Rajasthan and Kashmir — new unexplored regions till the late 19th and even 20th Century. The establishment of rail networks, a stabilised Colonial conquest of India enabled these travels.

An Indian Street Scene, Alfred Edward Emslie, watercolour on paper pasted on cardboard

Yet, Bombay is a key artistic city of the period for the artists who did stay behind. Cecil Burns would go on to head the Bombay School of Art (later Sir JJ School of Art) as will Charles Gerrard and John Griffiths. Griffiths would also work on the decoration of the now Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus and the High Court buildings. The Dutchman Marius Bauer would arrive in the city in 1898, and opt for help on his routes to Gwalior, Mathura, Vrindavan and Udaipur using a familiar city establishment, Thomas Cook. “They were a shipping company then, established in 1888. Not the tourist agency cashing travellers’ cheques as we know them,”

Tillotson adds.

Maratta Head, Horace Van Ruith, watercolour on handmade paper, c 1880

Art as fiction

Tillotson purposely earmarked the exhibition between two of the Subcontinent’s tumultuous years of political change — 1857 and 1947. Yet, the artworks eschew any portrayal of these social moments. To give context, Hiroshi Yoshida travels through India in 1930, the same year Mahatma Gandhi declares the momentous Civil Disobedience Movement.

Giles Tillotson

“It is the curious incident of the dog that did not bark in the night,” Tillotson quips, adding, “There is a sense in which all art is fiction, but these works were not aimed at engaging with societal change and change in landscape.” This is not to say that there were not Indian artists radically changing the landscape at the same time. “That is a story for another exhibition,” he concludes.

On May 1 to June 28; 11 am to 7 pm

At DAG, Mumbai Gallery, The Taj Mahal Palace, Apollo Bunder.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!