As poet Aamir Aziz asks for consent and remuneration for the use of his poem, marginalised artistes question the appropriation of their personal challenges

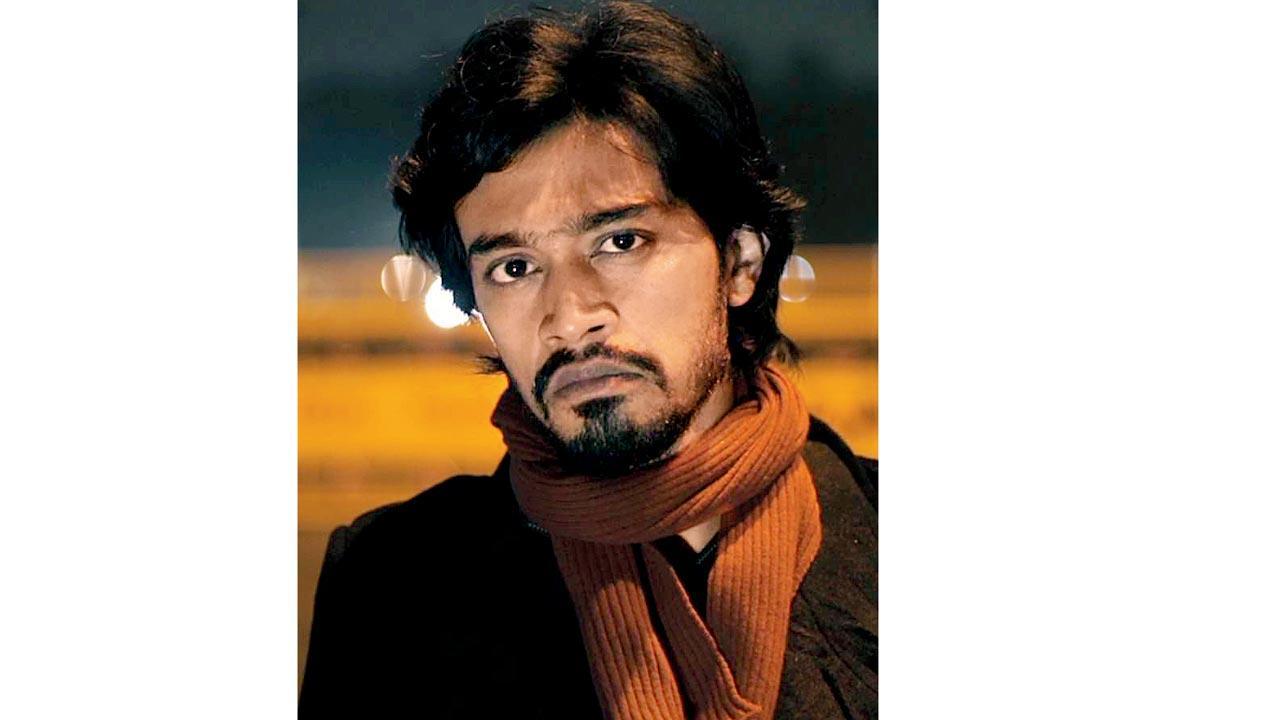

Aamir Aziz

In a recent controversy that unfolded on April 20, poet Aamir Aziz—best known for his searing piece Sab Yaad Rakha Jayega, written during the anti-CAA protests

in 2020—publicly accused renowned artist Anita Dube of using lines from his poem in one of her exhibitions without his consent, credit, or compensation.

“When I confronted her,” Aziz wrote on social media, “she made it seem normal—as if lifting a living poet’s work, branding it as her own, and selling it in elite galleries for lakhs of rupees was normal.”

Aamir Aziz first put out his original poem Sab Yaad Rakha Jayega—which was born out of dissent—during the anti-CAA protests in 2020. Pic/YouTube@The00aAamir

Aamir Aziz first put out his original poem Sab Yaad Rakha Jayega—which was born out of dissent—during the anti-CAA protests in 2020. Pic/YouTube@The00aAamir

Dube responded by acknowledging an “ethical lapse” in only giving credit, but not in checking with Aziz for using words from his poem. “However, I reached out and called him, apologised, and offered to correct this by [offering] remuneration,” she said in a private Facebook post. Dube went on to say that Aziz, instead of accepting her apology, chose to send a legal notice, and that she had to consult a lawyer as well. “As far as the accusation of my wanting to monetise the poem goes, I immediately took the works off sale,” she continued.

For centuries, marginalised communities across the world have turned to art for both refuge and resistance. But as urban mainstream spaces begin to embrace the aesthetics of dissent, a troubling pattern emerges. The rawness of protest art—rooted in lived experience—is increasingly repackaged by galleries, fashion houses, streaming playlists, and advertising campaigns. Stripped of its political context, what was once a cry against oppression is transformed into a curated experience, commodified for audiences who may never engage with the realities the work was born from.

Manan Shah

Manan Shah

“There is no formalised institutional system in place to address such allegations,” says Manan Shah, museologist, art curator, and writer. “However, when such concerns arise, it is imperative that the artist or gallery responds with care and sensitivity. The objective should be to reach a resolution grounded in mutual respect and understanding. If a community or individual artist expresses discomfort or withdraws consent for the presentation of their work—or a representation thereof—it should be promptly removed from the exhibition.”

Roshini Vadehra, the Director of the Vadehra Art Gallery, Delhi, where Dube’s controversial piece was displayed, told Sunday mid-day that the gallery only exhibits works that are directly from artists or have a very solid provenance. She clarifies, “In Dube’s exhibition, the context was always given. Credit was given to Aamir Aziz in the artwork caption and the curatorial note outlined the thought process behind the exhibition.” She adds, “That aside, in this case, there was a lapse in checking with Aziz on the use of his words in Dube’s artworks. These are things we don’t take lightly, and will be looking into it very carefully in the future.”

Anita Dube. Pic/Instagram@ vadehra-artgallery

Anita Dube. Pic/Instagram@ vadehra-artgallery

The Copyright Act of 1957 protects original artistic works, including paintings, sculptures, drawings, engravings, photographs, and works of artistic craftsmanship. This means that the creative expressions of marginalised communities, including traditional folk art, are eligible for copyright protection. However, the reality is that many individuals from these communities often lack institutional access needed to formally register their work, pursue infringement cases, or navigate the complex legal system. As a result, their art remains vulnerable to appropriation and commercial exploitation, despite the existence of legal safeguards.

The Aziz-Dube controversy has sparked a wider conversation about how intellectual property—especially when it emerges from marginalised voices—is frequently appropriated in the name of art, thereby undermining the very spirit of dissent it once embodied.

Aziz showcased Dube’s artworks that allegedly appropriated his poem in a post on X and wrote: “When I confronted her she made it seem normal—as if lifting a living poet’s work, branding it as her own, and selling it in elite galleries for lakhs of rupees was normal”. Pic/X@AamirAzizJmi

Aziz showcased Dube’s artworks that allegedly appropriated his poem in a post on X and wrote: “When I confronted her she made it seem normal—as if lifting a living poet’s work, branding it as her own, and selling it in elite galleries for lakhs of rupees was normal”. Pic/X@AamirAzizJmi

We spoke to artists from marginalised backgrounds, who tell us how they have navigated the tricky task of owning your narrative.

‘It is a blatant assertion of power’

Yashica Dutt, Author

There is a violence in the appropriation of protest art or resistance narratives, especially when they come from marginalised creators speaking about their own lives,” notes Yashica Dutt, a writer and journalist best known for her 2019 memoir Coming Out as Dalit.

According to Yashica Dutt, dissent can be commercialised ethically, but only if the original artist benefits and retains agency. Pic/Levi Mendel

According to Yashica Dutt, dissent can be commercialised ethically, but only if the original artist benefits and retains agency. Pic/Levi Mendel

Her story entered mainstream conversation once again after the release of Made in Heaven Season 2. In the fifth episode, The Heart Skipped a Beat, a Dalit bride played by Radhika Apte delivers a speech about her identity that closely mirrors Dutt’s own life and writing. Following the release, Dutt alleged that the show drew heavily from her personal story without giving her credit. The show’s creators, while acknowledging her broader contributions to Dalit discourse, overtly denied direct adaptation.

According to Dutt, this kind of erasure is not uncommon, especially as conversations around representation have only recently gained momentum in the Indian cultural sphere.

“The shift began post-2014–2015, particularly following Rohith Vemula’s death and the assertion of Dalit voices that followed. It extended to demands for the representation of Muslim voices, tribal communities, and others,” she says.

“This surge in representation is something we should celebrate. But it cannot come at the cost of marginalised creators themselves,” Dutt adds. “When we tell our stories, they often carry deep trauma. And that trauma, ironically, is what makes our stories so appealing to others—it’s what people want to showcase on screen.”

These stories, Dutt notes, take immense personal effort just to be told, let alone accepted by institutions or platforms. “That’s the Faustian bargain most artists from marginalised backgrounds are forced into. To unpack trauma and attempt to share it with a wider audience is incredibly difficult,” she says. “And when that deeply personal, hard-won narrative is appropriated—especially by dominant-caste creators, or people with more influence, access, or reach—it feels like theft.

Like a piece of our life has been taken without permission. And there’s nothing that these artists can do about it.”

According to Dutt, that’s what makes this a form of violence.

For her, and many others like her, it’s not just erasure; it’s a power play. “The process of creating these stories took years of struggle, pain, and persistence to tell—and someone else gets to take them, commercialise them, and gain from them, while we’re left with nothing,” she says. “That is a blatant assertion of power,” she adds.

She notes that when dissent is commercialised, the profit should flow back to the original artist, not to institutions or individuals who simply have more access. “Take Aamir’s poetry: used in speeches, protests, and banners, it empowers and unites. But when that same work is reproduced on merchandise or commercial platforms without credit or compensation, it becomes exploitative,” says Dutt.

The labour rooted in resistance is co-opted for profit, erasing the very struggle it represents. “Dissent can be commercialised ethically, but only if the original artist benefits and retains agency,” says Dutt.

‘How do you claim ownership of ancestral knowledge?’

Shilpa Mudbi Kothakota, Filmmaker, theatre practitioner, vocalist

THERE’S a danger in urban, disenfranchised people exoticising the art of communities they’ve long distanced themselves from” says Shilpa Mudbi Kothakota, a filmmaker, theatre practitioner, and vocalist who identifies as a Dalit Bahujan woman. “They often fail to truly understand the socio-political and geo-political dimensions behind these forms of art,” she adds.

Shilpa Mudbi notes that when an external artist samples a sound belonging originally belonging to a marginalised community and commercialise it, the original artist and hundreds like them are rendered obsolete. And the people who already have access and money and social capital benefit once again

Shilpa Mudbi notes that when an external artist samples a sound belonging originally belonging to a marginalised community and commercialise it, the original artist and hundreds like them are rendered obsolete. And the people who already have access and money and social capital benefit once again

Mudbi’s work draws heavily from Yellammanaata, an epic passed down through generations via music and theatre. Centred around Yellamma, a revered goddess in the region, the narrative is embedded in the collective memory of caste-marginalised communities in South India. Many of her songs are co-created, inherited oral traditions shared with her grandmother.

Last year, she discovered that songs unique to her community had been used in a Marathi play without permission or credit. They were sung incorrectly and falsely attributed to a theatre collective she was once associated with.

“There have been several moments when I’ve felt my work was being appropriated,” she says. “But this—what happened recently—was the last straw that finally pushed me to speak up. Honestly, these incidents are far too common.” The power of dissent lies not only in what is said, but in who says it—and why. Ignoring this reduces political art to mere aesthetic, further marginalising the communities from which it arose.

Mudbi explores the intersection of cultural heritage and performance through her work. “Many of our goddesses, especially in folk traditions, are depicted castrating or killing evil forces. This imagery reflects a long and fierce history of violence and oppression faced by their devotees. These devotees were never the sari-clad, gold-wearing archetypes, and so, neither were their goddesses,” she explains.

“Someone might take a Yellamma story and retell it in their classically trained voice, package it beautifully, and put it out without any intention of working with the actual community. That’s not representation—that’s extraction.”

She also observes that minority communities in India—particularly those whose native instruments and musical practices have not been absorbed into the classical mainstream—are often reduced to sources of musical sampling, with their traditions appropriated without recognition or context. “If you sample a sound and commercialise it, the original artist and the whole ecosystem around them—hundreds like them—are rendered obsolete. And the people who already have access and money and social capital benefit once again.”

Mudbi notes that even if you try to register your work, the system doesn’t know how to define collective ownership. “Say for instance you’re a Manganiyar artist, born into a community that has sung these songs for generations. How do you claim ownership of ancestral knowledge?”

The Protection of Traditional Knowledge Bill, 2022—which has been introduced in the Lok Sabha, but has not yet been passed—aims to protect traditional knowledge from misappropriation and recognise the rights of those who possess and generate such knowledge. It proposes the establishment of a National Authority on Traditional Knowledge and State Boards to oversee the protection and recognition of traditional knowledge.

Mudbi asserts that there needs to be a mandate for individuals who profit from the suffering of marginalised communities to compensate those communities. She cites the example of many savarna musicians from Maharashtra and Karnataka who have repeatedly gained popularity through their renditions of indigenous and tribal folk songs, musical beats, poetry, and more.

“These viral songs that are appropriated actually originate from the struggles of marginalised communities,” Mudbi notes. “Despite earning several lakh rupees per show, most artists never even acknowledge the song’s origins or credit the tribe they borrow from. Their success is built on the hardships of these communities—and it is crucial that they recognise and compensate them for their cultural contributions.”

‘Portrayal of Muslim characters in mainstream media has disturbed me’

Shahrukhkhan Chavada, Independent filmmaker

Independent filmmaker Shahrukhkhan Chavada, director of Kayo Kayo Colour—a feature film portraying the everyday life of a low-income Muslim family in Sodagar ni Pol, Kalupur, Ahmedabad—talks about the cinematic standpoint.

Shahrukhkhan Chavada (right) and his patner Wafa (left) drew inspiration from their own upbringing and struggles to create Kayo Kayo Colour

Shahrukhkhan Chavada (right) and his patner Wafa (left) drew inspiration from their own upbringing and struggles to create Kayo Kayo Colour

“The portrayal of Muslim characters in mainstream media is always something that has disturbed me,” he says. “They’re either shown to be too crass, or too noble. But we too are just people. We have the same daily routines as others, and it is this portrayal that I wanted to bring to the front through this film.”

He continues, “There’s a huge fallacy that surrounds most urban elite artists. They think that people who come from marginalised castes and classes are just subjects—that they cannot pen down their own stories, and so these artists must do it for us. It’s almost like the white man’s burden.”

The feature film was shot in the in Sodagar ni Pol area in Kalupur, Ahmedabad, and was created on the ethos of portraying the everyday life of a low-income Muslim family

The feature film was shot in the in Sodagar ni Pol area in Kalupur, Ahmedabad, and was created on the ethos of portraying the everyday life of a low-income Muslim family

Chavada adds, “I believe there’s nothing wrong with telling the stories of others. While it’s true that mainstream creators often hold more agency and social capital than us, it’s imperative that they approach the adaptation of our stories with greater sensitivity, portraying our struggles accurately without romanticising them.”

Chavada notes that they need to step out of their comfort zones and view the experiences of these communities with empathy—so that their stories aren’t reduced to commodities.

‘Even government institutions have contributed to this erasure’

Sachin Satvi, President and Founder of Adivasi Yuva Seva Sangh (AYUSH)

Warli painting, a traditional practice of the Warli Adivasi community in Maharashtra, faces rampant misrepresentation and commodification.

WARLI art which is a traditional practice of the Warli Adivasi community in Maharashtra, faces rampant appropriation and commercialisation while real Warli artists are pushed out—struggling to earn a livelihood and maintain their heritage

WARLI art which is a traditional practice of the Warli Adivasi community in Maharashtra, faces rampant appropriation and commercialisation while real Warli artists are pushed out—struggling to earn a livelihood and maintain their heritage

Sachin Satvi, President and Founder of the Adivasi Yuva Seva Sangh (AYUSH–Adivasi Yuva Shakti), highlights the increasing misuse: “Online platforms frequently promote training sessions conducted by individuals with no authentic ties to the Warli tradition. Many of these so-called artists copy and appropriate a handful of motifs or invent new patterns, branding them falsely as Warli art.”

These imitations often find their way into mass-produced products, further legitimised by books and videos that spread false information. Meanwhile, real Warli artists are pushed out—struggling to earn a livelihood and maintain their heritage.

Sachin Satvi

Sachin Satvi

“Even government institutions have contributed to this erasure,” Satvi says. “Warli paintings are often used indiscriminately to decorate underpasses, railway stations, public toilets, and footpaths—stripped of context, meaning, or respect for the art’s cultural and spiritual roots.”

“The consequences of such appropriation are severe: cultural misrepresentation, loss of identity, emotional distress within the community, economic exploitation, and the gradual erosion of our heritage,” sighs Satvi.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!