Tracing the journey of the Psychoanalytic Therapy & Research Centre in Mumbai, in the week of Sigmund Freud’s birth anniversary

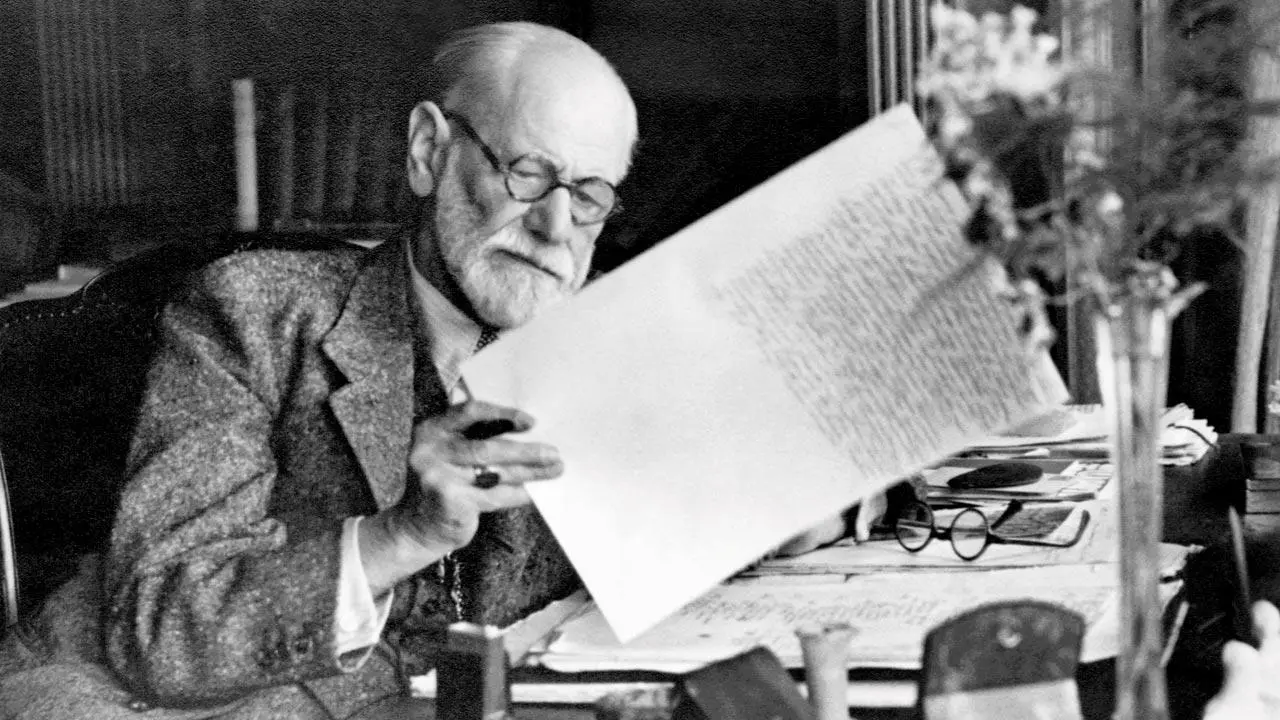

Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalytic therapy, at his home office in Vienna. Pic/Getty Images

In every consulting room, there ought to be two rather frightened people: the patient and the psychoanalyst. If both are not, one wonders why they are bothering to find out what everyone knows,” said British psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion.

In every consulting room, there ought to be two rather frightened people: the patient and the psychoanalyst. If both are not, one wonders why they are bothering to find out what everyone knows,” said British psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion.

A psychoanalyst describing such a challenging impasse, admits: “It’s two people being vulnerable together. I have seen a completely quiet patient stay uncommunicative for terrifyingly long. Gradually, he revealed to me the power of silence and we progressed.”

Making the unconscious conscious is central to psychoanalysis, introduced by the legendary Sigmund Freud (May 6, 1856–September 23, 1939), who changed perceptions of mental health and human behaviour with revolutionary theories of the unconscious mind.

Analysts Shailesh Kapadia, Aiveen Bharucha, Manek Bharucha, Minnie Dastur and Sarosh Forbes at a convocation. Pics courtesy/PTRC

Analysts Shailesh Kapadia, Aiveen Bharucha, Manek Bharucha, Minnie Dastur and Sarosh Forbes at a convocation. Pics courtesy/PTRC

The Indian Psychoanalytical Society (IPS) was established in Calcutta in 1922, three years after the British Psychoanalytical Society, and is affiliated to the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA). Helping to trace the history of the Psychoanalytic Therapy & Research Centre (PTRC), senior training and supervisory psychoanalyst Minnie Dastur explains that all training, academic and professional work is done by the Mumbai Chapter of the IPS. The PTRC runs its clinics, besides attending to administrative and accounting work.

The pioneer of psychoanalysis in the country, Girindrasekhar Bose, was a University of Calcutta psychology student. Subsequent to his 1917 doctoral thesis, “Repression”, he exchanged correspondence with Freud in Vienna, focusing on the Oedipus Complex. Though the two men never met, on Freud’s desk stood a Vishnu statue gifted by Bose.

Dastur says, “While Freud may not have always agreed with Bose, he was impressed by his intuition and interest. He put Bose in touch with Emilio Servadio, an Italian analyst here during the War years. Bhupendra Desai from Bombay came to study in Calcutta with Bose.”

Girindrasekhar Bose established the Indian Psychoanalytical Society in Calcutta in 1922; (right) Bhupendra Desai, who studied with Bose, primarily introduced psychoanalytic training in Bombay

Girindrasekhar Bose established the Indian Psychoanalytical Society in Calcutta in 1922; (right) Bhupendra Desai, who studied with Bose, primarily introduced psychoanalytic training in Bombay

Freud encouraged the setting up of the IPS in Bose’s home. Back in Bombay, Desai contributed to developing psychoanalytical training. The 1940s saw analyst Freny Mehta helm the Indian Council of Mental Hygiene, whose psychiatric social workers lectured at educational institutions. Mehta’s son-in-law Sarosh Forbes became a founder member of the PTRC.

The 1960s witnessed visits to the city from Kleinian analyst Dr Donald Meltzer and Martha Harris of the Tavistok Clinic in London. A little later, the eminent psychiatrist, Dr Manek Bharucha and his wife Aiveen qualified there, as did Dastur.

Aided by some enlightened industrialists, in 1974, the PTRC began operating in Bombay as a public charity trust. To set up a Tavistok training model in Bombay, the Bharuchas invited child analysts and psychotherapists like Gianna Williams, Gillian Ingall, Margaret and Michael Rustin. They formulated and registered a course of PTRC training, independent of the Tavistok brand.

Indian and Israeli participants at the Frances Justin International Conference, spearheaded by Micky Bhatia from India and Alina Schellekes from Israel

Indian and Israeli participants at the Frances Justin International Conference, spearheaded by Micky Bhatia from India and Alina Schellekes from Israel

A first office in Tardeo, in 1972, shifted to Horniman Circle before branching in Churchgate and Bandra. In 1999, the Centre introduced the Child and Adolescent Psychotherapy Training in India. Forbes forged ties with Australian colleagues for PTRC to engage in Indo-Australian Conferences, which the Israel Psychoanalytic Society joined.

“Psychoanalysis unlocks the past for patients to relive an unlived life,” asserts Dastur. “Today there is more sexual awareness, once undercover. Any crisis is just a trigger. Identifying the cause of trauma is uncomfortable. Without daring to confront innermost feelings, one cannot overcome grief, anxiety and depression. Avoiding this subterranean place creates earthquakes on the surface.”

Dastur emphasises PTRC keenly wants to make psychoanalytic therapy available to children and adults for all psychic disorders and emotional problems — “It is in-depth treatment going deep inside each person’s psyche, to reach pain that is attempted to be avoided through spurious means: addictions, confused and damaging relationships, conflicts within the self. Reach out and you will find a hand to hold you.”

Training analyst, teacher and supervisor Micky Bhatia had some experience overseas in the field of human rights and domestic violence. She returned with a Master’s in Counselling. Within 15 minutes of meeting Bharucha, she was disconcerted: “He felt I knew nothing and should study all over again. ‘You have a mind in your hands which can be seriously disturbed,’ he said. That vortex drew me in. A senior told me, ‘Analysis is another shot at life.’”

A psychologist and remedial educator in a school, Banu Ismail worked with children with special needs till the Bharuchas started the Observation Training Course. She says, “Training in child psychotherapy and adult psychoanalysis was transformative, providing an expansive understanding. It wasn’t simply learning a new method of treatment; the personal growth and insight were immense.” Aiveen Bharucha offered Ismail the role of director at the Horniman Circle outreach clinic, committed to patients unable to afford private fees.

The transfer to personal enhancement has similarly rewarded Nuzhat Khan, who takes candidates in training for their personal analysis, is part of the teaching faculty, and a supervisor for students’ clinical work — “What keeps me going is the need to pass on as best I can the invaluable training that was given to me. Being with PTRC has taught me it is possible to conduct one’s life with the same attention and thoughtfulness as one might do in a session.”

Vital PTRC initiatives include the Young People’s Counselling Service — a briefer model of four to six sessions addressing immediate concerns of young individuals not ready for long-term psychoanalysis. The Infant Mental Health Programme of short therapeutic interventions for children under five also supports parents struggling with practical adjustments to parenthood.

Dissatisfied with her Economics degree, Zarine D’Monte qualified in Psychology, worked with a paediatric neurologist and signed up with PTRC. While enjoying analysis with children and adults, she finds teaching the Infant Observation course most fulfilling. Trainees observe a mother and new-born interact over two years. “The mother’s capacity to emote with her baby, anticipating every need, is fascinating. There can be mis-attunement between them too. But as the British psychoanalyst DW Winnicott said: As long as there is a good enough mother.”

D’monte’s wish list for PTRC prioritises mother-infant work, even setting up mother-infant clinics. “Individual personality forms in infancy. In the earliest interaction between mother and infant, the latter learns about relationships. This relationship is a template to those that follow. It is almost prophylactic work. Prevention is better than cure.”

Practitioners unequivocally assert that psychoanalysis cuts into the heart of difficulty, treating underlying problems, not merely symptoms. Ismail says, “There is something very real and true about psychoanalysis. The setting is structured, but the free association gives patients a space to emote their feelings. Meeting four to five times a week allows continuity in the thinking that allows patient and therapist to work closely.”

Another training analyst and training supervisor with the Mumbai Chapter of the IPS, Gouri Salvi, says, “The ‘too frequent’ sessions — intensive analysis — are perhaps not necessary for all, yet make significant improvements in a number of cases. Working through emotional difficulties at an early age makes adult life much easier to navigate.” Now living in Goa, Salvi qualified here as a child and adult psychoanalyst. Bringing out the PTRC newsletter since its inception, she will be handing it over to a younger editorial team.

Every year, an influx of bright, curious students from diverse backgrounds brings fresh energy and perspectives. A qualified student of the IPS becomes a member of the IPA. The practice of psychoanalysts and the Mumbai Chapter’s training programmes going online during COVID, opened up access to patients and aspiring students outside the city. No longer a taboo topic, mental health is spoken about freely. The need for its services has peaked post-pandemic.

Manju Mukhi oversees counselling programmes extended to city institutions like Cardinal Gracias High School, Alexandra Girls’ School and Sir Cowasjee Jehangir School. Therapists conduct workshops with extremely distressed, underprivileged children.

Highlighting how psychoanalysis, art and myth are related, the Continuing Professional Development Cell organises events which students, analysts and the public attend. PTRC students present short papers to assess art, film and literature through a psychoanalytic lens.

“Our PTRC training is as great as any internationally,” says Bhatia, adding, “I used to believe interpretations had to be brilliant to be effective. Patients have taught me that the simplest, most ordinary observation can open up a whole inner world.”

Reach PTRC on 9321834505

May 6

The day Freud was born, in 1856 in Freiberg, Moravia (Czech Republic)

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!