Asexual individuals, or aces, say most people find their sexual orientation mind-boggling, but the community leads rich, emotionally fulfilled lives. We ask them how they live and love when sex is off the table

Illustration/Uday Mohite

On the day of my wedding, everyone was happy except for me,” says Harsh K, 33. “For three years, there had been a lot of pressure on me to get married, but I dreaded the thought of the wedding night. I didn’t know how to explain to my parents that I am asexual,” says the accountant from Thane, who has since separated from his wife.

Asexuality is a sexual orientation in which an individual experiences little to no sexual attraction. Harsh is not alone; while it is a small community, there are more asexual people (aces for short) than one might expect. According to Statista, one per cent of the global population is asexual. “Based on that percentage, the ace community in India estimates there are 1.45 crore of us in the country,” says Harsh.

Despite growing LGBTQiA+ awareness about, ace erasure and acephobia sadly remain rampant both outside and within the community. On April 6, observed as International Asexuality Day, renowned Harry Potter author JK Rowling took to social media claiming asexuality isn’t real, and that aces are just “straight people who don’t fancy a quickie”.

Naina Shahri and Dr Kanchan Pawar

“I grew up reading Harry Potter and watching the movies. Now, to hear a childhood idol mock my identity is so hurtful, but it is what I have come to expect from people,” says Harsh. “I have only once tried telling someone — my childhood friend — that I am ace. I thought he would understand as he is gay. But he just told me I would feel sexual attraction once I met the right person,” he recalls, adding that he now regrets not having confided in his wife before their nuptials in 2019.

“There was a lot of parental pressure on my wife and I to have kids. And of course, my wife too had some expectations, but I could not meet them. It caused a lot of friction in the family. Eventually, I came clean to her and she filed for annulment of our marriage. My family still hasn’t come to terms with it. They took me to doctors, suspecting I was suffering from some medical issue, but this is just who I am,” says Harsh.

“In my experience, Asexuality is a valid sexual orientation, but there are very few people who are aware that this could be their sexual orientation. Most [patients] visit complaining about little to no desire for physical intimacy, or their partner complains about it and they feel guilty,” says Dr Kanchan Pawar, a queer-affirmative primary care physician based in Pune and medical advisor for Ally Heart.

“I do advise investigations, if necessary to rule out hormonal and other issues, if the history suggests otherwise. In general, I encourage clients who are confused or ambivalent to not hurry to label themselves as identifying with a specific gender identity or sexual orientation. It’s a process of self discovery and acceptance, guided by empathetic non-judgmental counselling,” she says.

It causes immense damage to aces when they are dismissed even in quarters they expect to find safety in, such as the queer community, or therapists and doctors. Unfortunately, this is all too common. “A lot of asexual folks I’ve spoken to have faced this — being told that their orientation is just a trauma response. That’s not just incorrect, it is also harmful,” says Naina Shahri, a queer-affirmative therapist, “Asexuality is a valid orientation; it’s not a phase or dysfunction, and it doesn’t need to be explained or fixed. Yes, trauma can affect one’s relationship with sex, but it is deeply problematic and incorrect to assume asexuality stems from trauma.”

“Aces struggle to find spaces where they feel safe, accepted and experience a sense of belonging. Being excluded even from queer communities leads to further isolation and loneliness,” she adds. Asexuality can be especially difficult to wrap our head around as a society that is so prominently driven by sex, marriage and procreation. “My friend had asked me, ‘Don’t you want love?’ I told him, ‘If sex can exist without love, then why can’t love exist without sex?’ For years, I felt like no one would understand, but last year, I finally found understanding, and love, with my girlfriend, who is also ace,” shares Harsh.

He still gets curious, sometimes intrusive questions from friends who want to know how their relationship works. “I don’t think it’s anyone’s business, honestly, but I still answer because it might help people understand aces better,” he says, “The most common question we get is how do we experience intimacy if we don’t have sex. To which I say, there are different kinds of intimacy. My partner and I are big on sensual intimacy—hugs, kisses, skin-to-skin cuddling. And there’s emotional intimacy that all couples crave; we are each other’s safe space and favourite person. She is the person who truly sees and knows me; there’s nothing more intimate than that.”

The sweetest ace icon: Cake

The ace community adopted cake as its symbol after it became a commonly used analogy online on the Asexuality Visibility and Education Network. Many use cake to explain their orientation: “Cake is wonderful, and while many people like it, some don’t, and the same goes for sex”. Others explain that to them, cake is better than sex.

‘How to talk about it when sex itself is taboo?’

Abhramika Choudhuri, 25

Management professional

Ace, non-binary, hetero-romantic

I discovered I was ace during the COVID-19 lockdown in 2020, when I came across the term online and related to it,” says Thane-resident Abhramika Choudhuri. “I am a very romantic person, but until then, I had a certain idea of what relationships are like based on what I had read or watched in mainstream media, where sex is played up so much. At first, I was afraid that I would never find a partner, or that my partner would have to compromise on their own sexual needs to be with me.”

Abhramika Choudhuri is a true romantic, and says her love language with both her partner and friends involves physical touch. Pic/Ashish Raje

This fear, in great part, stemmed from her first relationship where she faced sexual abuse from her partner. “Aces are significantly more prone to facing sexual assault in relationships because they are constantly being convinced that they are ‘broken’,” Choudhuri says.

When she was about 20 years old, Choudhuri came out to her family. Ironically, one of the roadblocks she faced while coming out was “how to talk about asexuality when sex itself is taboo while talking to Indian parents”. “I was open about sex with my mum, and she tried to be understanding. I came out to my dad a little later, over a long email. We have never spoken about it, but he has never treated me differently because of it.”

In 2023, Choudhuri had her first taste of what a healthy relationship could look like. “I told him at the outset that I was ace and, to my surprise, he already knew what that meant. He told me he wanted to be with me and could do without sex. Because of that safe space, with him, I also got a chance to explore what kinds of physical intimacy I enjoy,” she says.

“A huge part of my love language is physical touch; I got the chance to explore kissing, cuddling without the implication that it would lead to sex,” she shares. It’s important to note that taking sex off the table doesn’t mean that aces don’t have a complex and varied relationship with love and sensuality. “A lot of aces fantasise but might not act on it. Some aces who aren’t sex-averse might also be willing to act out their fantasy in a partnership that feels safe and respects their boundaries,” says Choudhuri. And what does she fantasise about? “Sometimes I fantasise about cooking in the kitchen while my partner grabs me by the waist from behind and kisses me.”

A 2016 study of 351 asexual people and 388 sexual participants conducted at the University of British Columbia in Canada found that nearly half the ace women, and three-fourths of ace men have sensual or sexual fantasies and masturbate. Notably, both asexual and sexual participants were just as likely to fantasise about topics such as fetishes and BDSM, the study found. At community gatherings or panels, “aces have mentioned fantasising about things as varied as submissive-dominance play or even just holding hands. It depends on what they like, and makes them feel safe”, says Choudhuri.

‘I do feel the need for a partner’

Shilpa Kamble, 36

Genetics consultant

Ace, hetero-demiromantic

Generally, people figure out if they are ace in their 20s, but I was 32 when I realised it,” says Shilpa Kamble. That’s partly because the Navi Mumbai-resident spent her 20s utterly focused on her career, and was content with her life as an independent, young woman. “Now, though, I feel the need for a companion” says Kamble.

Shilpa hopes to some day find a partner with whom she can adopt a child. Pic/Atul Kamble

She recalls a relationship in her youth that ended because she was not comfortable getting physically intimate. At the time, she had chalked it down to youth. “Then, during the COVID-19 pandemic, I consulted a psychologist regarding professional ups and downs and the discussion led towards the fact that did not experience sexual attraction towards any gender, which makes it difficult for me to think about any relationship.

The psychologist told me about asexual orientation. I found relief after realising I identify as asexual. I found the Indian Asexuals community set up by Raj Saxena, and found others like me,” she recalls. When she came out to her family, her sister told her, “This disinterest in sex happens to all women”. “She told me, ‘Once you get married, you will settle down’. It took time for my family members to understand it,” says Kamble.

There were some questions over whether it was a hormonal imbalance issue. “During my mid-twenties, I was also facing PCOS. I was prescribed hormonal medication which did regularise my menstrual cycle and other symptoms, but did not affect sexual attraction. Asexuality has nothing to do with hormones,” stresses Kamble.

She eventually went on to date a couple of people from the Indian Asexuals group. But like any relationship, there were challenges. After all, not all aces are the same. “When trying to meet other asexuals, being antinatalist [not wanting biological children], I found it difficult to find a partner as there was always a pressure to have biological children from the men I talked to and their families. Later, I realised men do not come out as asexuals to their family. I don’t judge them; men face more stigma when they come out as ace because it raises questions on their masculinity,” says Kamble, who says she hopes to some day find a partner whom she can adopt a child with.

‘Dating as an ace is very difficult’

Raj Saxena, 31

Assistant professor of fine arts

Ace, homo-romantic

Most aces discover their sexual orientation in their 20s or 30s. Raj Saxena was just 17 when he realised there was something different about him. “I was working at a call centre, and colleagues would sometimes watch porn after their shift. It disgusted me. One of them showed me gay porn, and while the sex still repulsed me, I realised that I feel romantic attraction to men,” he recalls.

Raj Saxena founded the Indian Asexuals online forum in 2013. It now has hundreds of members

But Saxena still didn’t have the words to describe what he was experiencing. “At that time, I thought the ‘A’ in LGBTQiA+ stood for ‘Ally’.” he says. “Dating as an ace is very difficult, more so if you are homo-romantic,” says Saxena. “Dating apps are all about hooking up for sex. Not all aces reject sex; it is a spectrum. Some are sex-favourable if there is an emotional bond [demisexual], while some are completely sex-averse. But there will always be men who will say things like, ‘Just try me, I will change you from asexual to sexual. And the gay community, especially, is hypersexual.”

“In the beginning, I tried dating apps. In 2013, one man I met locked me in a car and tried to force me into sex. I yelled and fled. This made me so afraid, I deactivated all the apps,” he recalls. Saxena then went to a therapist, who told him his asexuality was “just a phase” and a “trauma response”. “It was very disheartening to hear that from a counsellor. But I went online and found some research material about asexuality,” recalls the Agra resident.

At a time when few in the world — let alone India — even knew the word, Saxena set up the country’s first online forum for the community, Indian Asexuals, in 2013. Hundreds of aces are part of this community and have gone on to find love with each other through its WhatsApp group chats, and matchmaking initiatives. Some of these services are chargeable, most are not.

“Asexuals are like a minority within a minority,” says Saxena, “Even in the queer community, aces are perceived as weird because we don’t want sex. People think it’s the same as celibacy; celibacy is a choice and asexuality is not.”

The dating game is riddled with anxiety for aces. “We have to keep confirming, ‘You are okay if we never have sex, right? You are not expecting me to change my mind later?’ I’ve dated people who pretended to be aces too for a few months, and then started sending me porn clips, saying they want to try the same position,” says Saxena, who is currently single.

Some aces have found a middle ground in open or polyamorous relationships. “Their need for love and emotional bonding is met, and their partner can meet their sexual needs with someone else. Some aces, like me, don’t want to share our partner. The ace community is diverse, including whom we are drawn towards–some are drawn to men, some to women and others yet may be pan,” explains Saxena.

“Sometimes there are problems even if you find another ace, because they may not be out. Whoever I date in the future has to be out. I want us to meet each other’s families, holiday together, buy each other flowers, go out to romantic dinners. I don’t want to hide who I am.”

Glossary of terms

Amatonormativity: The societal assumption that everyone desires an exclusive romantic relationship and/or marriage

Allosexual: Individuals who experience sexual attraction to others

Asexual: Individuals who don’t experience sexual attraction to others

Demisexual: Individuals who only experience sexual attraction after an emotional bond

Graysexual: Individuals who experience infrequent or low-intensity sexual attraction

Sex-favourable: While some aces are repulsed by sex (sex-averse), some do not mind sex with their partner (sex-favourable)

‘Aces fantasise, pleasure themselves too’

Oviya V, 19

Author, educational activist

Aromantic-asexual; agender

In school and college, everybody talked about romance, dating and sex. I’d think to myself, ‘I understand some of the emotional and sensual connections you’re talking about, but I don’t quite get the appeal of sex itself or being someone’s romantic partner exclusively’,” recalls author and activist Oviya V.

Oviya V was just 17 when she realised she was aro-ace. She wrote a book, Being AroAce: Insights and Representation, to explain the nuances of the community

They identify as aromantic-asexual (aro-ace), which means they don’t experience romantic or sexual attraction towards any gender. What they do experience is alterous (a form of emotional attraction) attraction or “the desire to have a special emotional connection with someone and to spend quality time with that person”. They also experience sensual attraction, which is the desire for physical touch and closeness.

How is this different from a romantic relationship? “Feeling ‘butterflies’ or emotional excitement at the thought of dating them, wanting to go on romantic dates, wanting to be someone’s special romantic person and being excited by it — this doesn’t apply to me,” they explain.

In alterous attraction, “you get emotionally intense about people but recoil at romantic expectations”, they say, recalling how, at the age of 17, they first realised they might be ace: “I liked this person, and told them about it, but I also hoped they would not reciprocate. Just the thought of being in a romantic relationship and being their ‘girlfriend’ gave me the ick. I was confused by my own reaction, so I started researching and came across the term aromantic and alterous attraction and it began to make sense.”

All the same, it’s not like aro-ace people don’t want relationships; it just has to respect their boundaries and needs. “People think that if you’re aro-ace, you are incapable of emotions and love, and don’t ever want a relationship — that’s nonsense. Everyone seeks and deserves love, but there are different ways to get there,” says the teen author who has written about the aromantic asexual community in her book, Being AroAce: Insights and Representation.

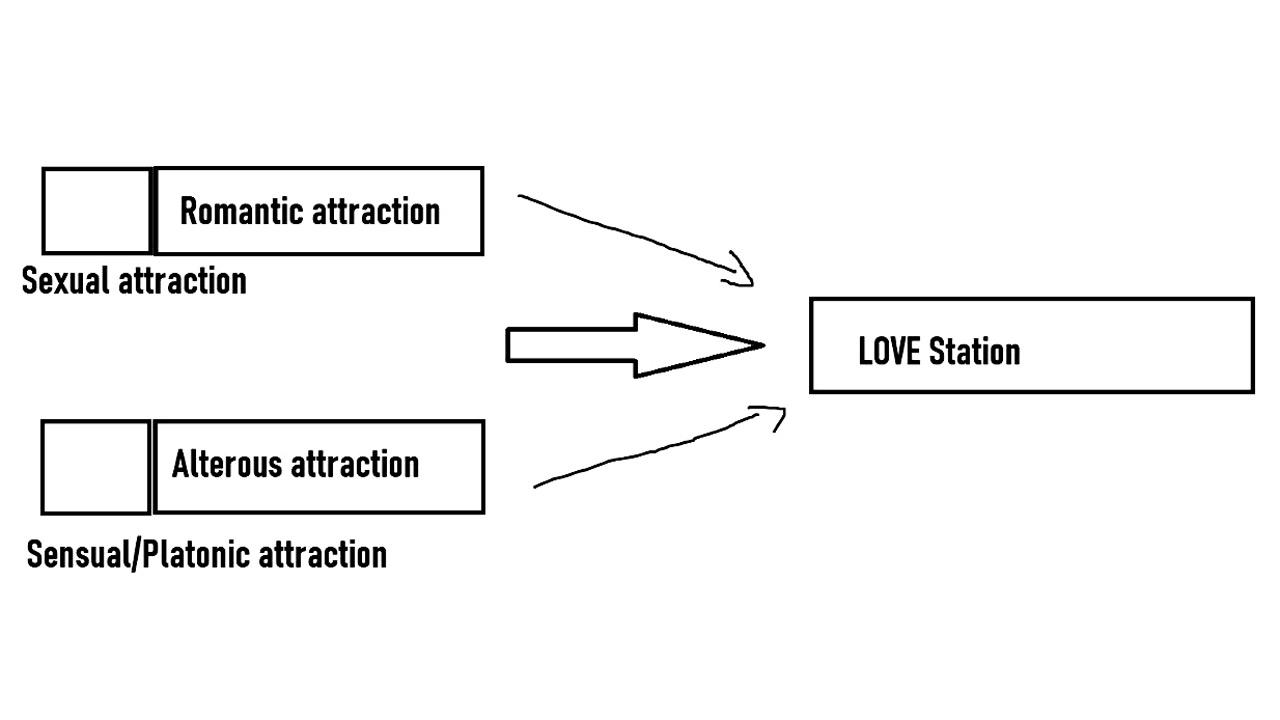

Romantic attraction is just one of the paths or trains that lead to love, just as alterous attraction, Oviya explains while drawing us a diagram

“There’s a big misconception that romantic attraction is the same as love; it is just one of the paths that lead to love,” they say, while drawing us a picture of two trains, one labelled “romantic attraction”, the other “alterous attraction”. “The forms of attraction are different, but both are headed to the same station: Love,” they explain, “You can add a sexual attraction bogey to the romantic train [the standard depiction of relationships in mainstream media], or a sensual attraction bogey to the alterous attraction [Oviya’s experience], but the destination stays the same — LOVE.”

What would Oviya’s ideal relationship look like? “I would love a queer platonic relationship [QPR], where my partner and I define the rules. Unlike friendships which are strictly platonic, and romantic relationships which are based on romance, QPR can have various attractions such as alterous, intellectual, sensual — whatever the partners agree on. A QPR is an exclusive relationship that can sometimes lead to marriage. Some day, I’d like to adopt a daughter with my partner.”

It’s also a myth that asexuality refers to low libido; “they are not connected,” stresses Oviya. “Many aces have a sex drive, it’s just not tied to sexual attraction to others. Many aces fantasise, many of them pleasure themselves,” they confide.

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!